The state of the online counterfeit market is shifting. Reflecting on U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s seizure of $8 million worth of fake Cartier Love bracelets early this year, following its confiscation of an estimated $1.3 billion in counterfeit goods – from fake Nike x Jordan sneakers to Gucci handbags – in 2020, Thomas Mahn, Customs’ Port Director in Louisville, Kentucky, said just that. “Driven by the rise in e-commerce,” he noted that “the market for counterfeit goods in the United States has shifted in recent years from one in which consumers often knowingly purchased counterfeits to one in which counterfeiters try to deceive consumers into buying goods they believe are authentic.”

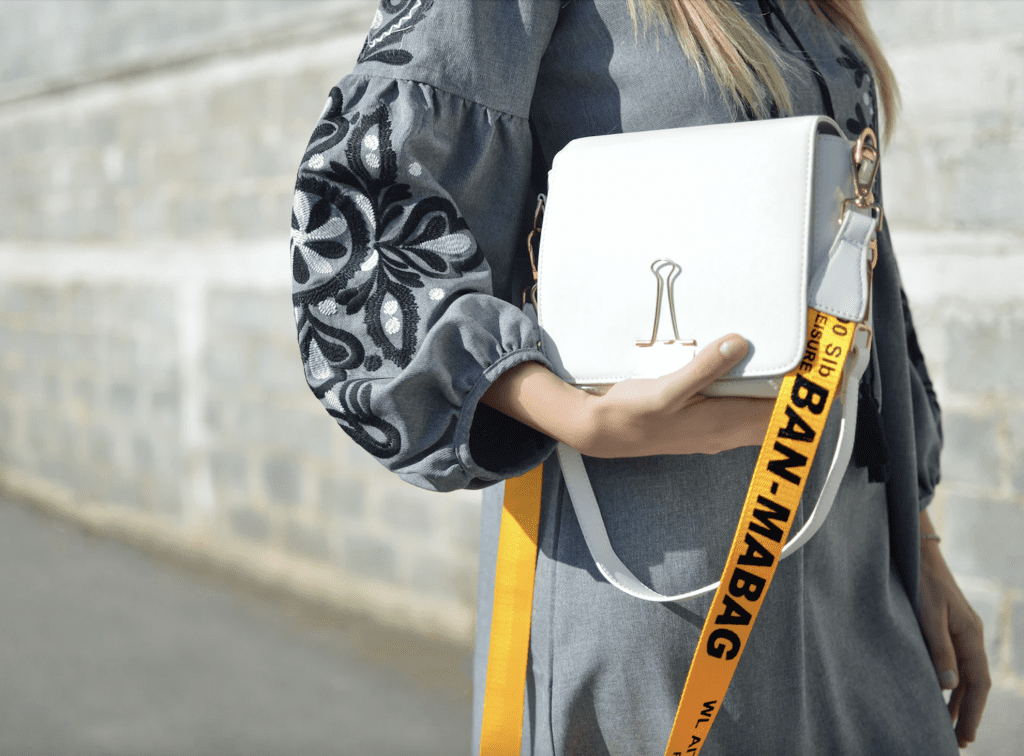

This sentiment is seemingly backed up by a recently-released report from the European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”), which found that nearly 10 percent of consumers in the EU – or almost 1 in 10 consumers – revealed that they have been misled into buying counterfeit goods or services over the past 12 months, and as many as 33 percent stated that they have wondered whether the products/services they purchased were, in fact, the real thing. This uncertainty is particularly relevant “when it comes to online marketplaces, where counterfeit goods are made to appear ‘real’ through unauthorized use of the brand owner’s own marketing product photographs and/or descriptions,” according to international patent and trademark consultancy Novagraaf.

Whose responsibility is it?

Not long after the EUIPO released its report, the International Trademark Association (“INTA”) issued a report of its own, entitled, Addressing the Sale of Counterfeits on the Internet, in which it discusses the rise in online sales of counterfeit goods, noting that “how to address the sale” – and the scale – “of counterfeits on the Internet has become a hotly debated topic within industry and among policymakers, alike,” and that questions loom about “who is responsible for curbing the problem and what legal, policy, and/or voluntary measures are needed have been widely discussed in industry and government forums.”

In its report, INTA proposed that online marketplaces, in particular, as well as other service providers – including search engines, logistics companies, and payment processing providers – are among those that are in the best position to stop counterfeiters because of “the direct relationships they have” with counterfeit-selling entities. In addition to identifying key players in its June 2021 report, the trademark body also called on marketplace sites and others “to address practices and algorithms [that they employ] that may also be exacerbating the problem.”

Among its key recommendations, INTA asserts that online marketplaces should take more responsibility for verifying the identities and addresses of their sellers, and improving their disclosure policies to facilitate access by brand owners and law enforcement authorities to seller identities. “Online marketplaces should utilize ‘know your customer’ measures to verify the identities and addresses of sellers and improve disclosure policies to facilitate access by brand owners and law enforcement authorities to information about counterfeiters, including seller identities,” INTA contends.

As of now, “Counterfeiters have the ability to remain anonymous when posting items for sale, as virtually every aspect of the sales process can be performed using false or incomplete names.” This is important, according to Novagraaf, as “counterfeit networks often operate multiple and seemingly unrelated stores across online marketplaces in order to disguise the size of their operation.” In other words, “If one store is removed, there is very little real financial impact for the counterfeiters.”

In terms of search engines, INTA claims that in connection with their advertising services, these companies should have “a clear and effective complaint process publicly available to report ads for counterfeit products and facilitate efficient filtering and takedown processes in an ongoing, proactive fashion.” Meanwhile, payment service providers should have in place policies prohibiting the use of their services for the purchase and sale of goods that are determined to be counterfeit under applicable law, according to INTA, and social media sites should not only “use a proactive filtering program to facilitate the removal of postings that advertise the sale of counterfeit merchandise,” they should also work to verify the identity of their users offering for sale counterfeit merchandise, and provide these details upon request to brand owners whose rights have been violated.

The role of rights holders

While both the INTA and the EUIPO reports center on the important role to be played by online marketplaces in the fight against counterfeiting, Novagraaf notes that “they are also clear that brand owners, brand organizations and intermediaries also have an important role to play,” including in a collaborative capacity with the aforementioned marketplaces and service providers, such as the partnering of Amazon with an array of brands in anti-counterfeiting lawsuits and Gucci’s joint lawsuit with Facebook. Part of this is “the need for consumer education,” which appears to be part of what is going on in the lengthy complaints and corresponding legal battles initiated by the likes of Amazon. The quest to build consumer and brand trust by way of positive PR is also underway in connection with these cases, of course.

The other piece, per Novagraaf, is “proactive monitoring and enforcement across both established and up-and-coming platforms.”

Changes are coming

With the foregoing in mind, it is worth noting that changes in the marketplace landscape may be coming, as lawmakers in the U.S., for instance, are pushing for at least one new bill that could require online marketplaces to verify and disclose third-party seller information to consumers. Following a similar attempt in the House of Representatives and before that, an earlier bid in the Senate, the Integrity, Notification, and Fairness in Online Retail Marketplaces for Consumers Act (the “INFORM Consumers Act”) was reintroduced in the Senate in March in an effort to “combat the online sale of stolen, counterfeit, and dangerous consumer products by ensuring transparency of high-volume third-party sellers in online retail marketplaces.”

Specifically, the INFORM Consumers Act would require online retail marketplaces in the U.S., such as Amazon, to authenticate the identity of “high-volume third-party sellers,” i.e., sellers that have entered into 200 or more discrete transactions in a 12-month period amounting to an aggregate total of $5,000 or more. To confirm the identity of these third-party sellers, the bill requires online marketplaces to acquire sellers’ government-issued photo identification, tax identification number, bank account information, and contact information on an annual basis.

Beyond that, the bill would call on online retail marketplaces to disclose to consumers the seller’s name, business address, phone number, email address, and whether the seller engages in the manufacturing, importing, retail, or reselling of consumer products, and would mandate that online marketplaces provide contact information for customers to report potential issues, “such as the posting of suspected stolen, counterfeit, or dangerous products.”

Changes are also expected when it comes to online marketplace takedown practices in the European Union, Novagraaf asserts, pointing to the forthcoming Digital Services Act, which it says “adds new opportunities and risks to online brand protection strategies.” For this reason, the consultancy encourages “brand owners to prioritize online brand protection solutions that offer dedicated, marketplace-specific takedown workflows that are both automated and tailored to the legal issue encountered.”

These solutions also enable brand owners and their advisers “to work more effectively with online marketplaces, thereby upholding their intellectual property rights and valuable brand goodwill, and protecting their customers.”